She had been seven months pregnant with her fourth when her husband called her inside. He wanted to talk. His slacks swished as he walked to and fro, his hair smoothed into place with Bryl Cream. “I have enlisted,” he said gruffly. “They will need medics.” Murta’s heart sank. Rex, Robert and Clint had signed up too. He coaxed her to have the baby induced. He demanded to meet his child. He held the boy to his face, and grunted in approval.

‘Darwin is under attack! Get the hell out of Bowen! Do whatever you can to make it to Sydney,” his cable read. Murta grabbed her keys, her four boys, and drove like hell. She wondered if the sky was going to fall, the world end. The dirt roads were horrific, and the newborn wailed. She cut a path through cane fields and rampant bush. She exchanged her jewellery for fuel. She arrived home to Sydney, and sank to the green axeminster carpet. She prayed it might swallow her. Clint and Robert had been killed, and Rex was badly injured. Murta wept and stroked the picture of the boys on the mantle. Ma Ma arranged to have a stained glass window erected in their church. It featured Sir Galahad in his armor, his face that of a young man, unbroken, unyielding, perfect.

The war had made accommodation scarce. She was vying for a granny flat with another lady. The woman noticed the softly-spoken boys assembled in a line behind the fey. “You take it love, you need it more than I,” she smiled at Murta. Murta found work off Broadway, training as a secretary at an export house. She remained there until the late 1970’s.

Rex hobbled, his hip shattered in the war. He and his wife had been Murta’s dear friends until their death’s in the early millennium. Rex would help the homeless in a soup kitchen connected to the church. He used to pause at the stained glass window, tracing the outline of Sir Galahad.

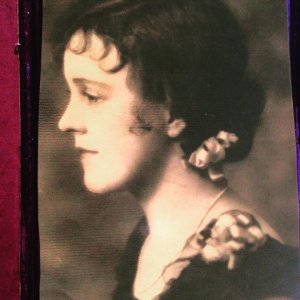

Murta loved tequila, tiramisu, honey, chocolate and steaming-hot coffee. When you sauntered back home at a hundred years of age, it was still a shock. I expected that you might live forever. Thankyou for your adventurous spirit (which saw you misbehave to such an extent that your father sent you on a boat to England). Your adventurous spirit saw you learn to drive, and with a friend, make your way to Scotland as a teenager! The brave Knight and fair maiden ventured deep into the ocean. The folks that have been invigorated with the spray of their concern rest on the sand. Rex, Robert and Clint hold hands with Murta. They are plunged into the lupine liquid, and the ocean carries them away.